Spare

That Shrub Spare

That Shrub

–

Do Your Part To Control Erosion

|

Rain

has long been the single word most identified with the Puget

Sound region. In a watershed that consists largely of forest

land and farmland, most rain soaks slowly into the ground and

gradually drains to nearby surface waters or into the groundwater.

As forests and hillsides are cleared and wetlands are filled

for development, more of the water runs off instead of soaking

into the ground. As the Puget Sound basin has developed, changes

in land use have increased seasonal flooding. |

|

|

Roofs, roads,

parking lots, sidewalks, driveways and other hard surfaces are

impervious to rain. Virtually all of the rain that falls on these

surfaces has nowhere to go but downhill, fast. As a result, flooding

increases in frequency and severity. A short, intense rainstorm

that only slightly raised water levels in the past, now turns

a stream into a torrent. The speed of water moving across the

land and in the streams increases and accelerates soil erosion.

Much of the

soil washed off vacant lots, cleared land, uncontrolled construction

sites, and from road cuts is carried into streams and can eventually

reach Puget Sound. In streams, this sediment smothers plants and

animals that live in the shallows and clogs the clean gravel needed

by spawning salmon. In bays and inlets of the Sound, this sediment

smothers lingcod spawning grounds and eelgrass beds. This runoff

may also include a variety of pollutants. Metals from downspouts

and pipes, paints, brake linings, engine drippings and tires join

nutrients from lawn fertilizers, detergents, animal wastes, and

failing septic tanks. Bacteria and oxygen-demanding substances

from farm animal and pet waste, failing septic systems and combined

sewer outflows are carried downstream by the runoff. As if these

weren’t enough, oil and grease from parking lots, roads, service

stations and illegal disposal of waste oil into storm drains combines

with other toxic chemicals that may be released from industrial

and commercial businesses.

Dealing

with Surface Runoff Dealing

with Surface Runoff

What can be done to treat these rainy day blues? Natural wetlands

slow the flow of runoff and filter pollutants from the water passing

through them. Help to preserve wetlands in your neighborhood and

throughout Puget Sound. When development occurs, insist that best

management practices be used. These include detention ponds which

allow pollutants to settle, infiltration devices which channel

runoff through the soil layer, and grassy swales which use vegetation

to filter runoff.

Reduce

your use of impervious surfaces. Use spaced paving stones instead

of concrete, ground cover instead of grass, and pervious asphalt

instead of standard. Reduce

your use of impervious surfaces. Use spaced paving stones instead

of concrete, ground cover instead of grass, and pervious asphalt

instead of standard. |

Plant

grass along and in drainage ditches or channels to slow the

rate of runoff and help filter pollutants. Plant

grass along and in drainage ditches or channels to slow the

rate of runoff and help filter pollutants. |

Where

impermeable surfaces are used, divert rain from the paved surfaces

onto grass or into vegetation to permit gradual absorption. Where

impermeable surfaces are used, divert rain from the paved surfaces

onto grass or into vegetation to permit gradual absorption. |

Use

grass-lined swales, berms, and basins to control runoff on your

property, reduce its speed, and increase the time over which

the runoff is released. Use

grass-lined swales, berms, and basins to control runoff on your

property, reduce its speed, and increase the time over which

the runoff is released. |

Preserve

the established trees around your home and in your neighborhood.

Plant new trees and shrubs to encourage excess rainwater to

filter slowly into the soil. Plant and maintain a vegetated

buffer strip at the base of steep slopes and along water bodies. Preserve

the established trees around your home and in your neighborhood.

Plant new trees and shrubs to encourage excess rainwater to

filter slowly into the soil. Plant and maintain a vegetated

buffer strip at the base of steep slopes and along water bodies. |

Resod

bare patches in your lawn as soon as possible and minimize bare

soil in your garden to avoid erosion. Resod

bare patches in your lawn as soon as possible and minimize bare

soil in your garden to avoid erosion. |

Install

gravel trenches along driveways or patios to collect water and

allow it to filter into the soil. To be most effective, trenches

should be one foot wide by three feet deep. Grass swales, low

areas in the lawn, can be used to move water from one area to

another. Install

gravel trenches along driveways or patios to collect water and

allow it to filter into the soil. To be most effective, trenches

should be one foot wide by three feet deep. Grass swales, low

areas in the lawn, can be used to move water from one area to

another. |

If

you build a new home, ask your builder to leave as much of the

original vegetation as possible on site. Before you start construction

grading, acquire a copy of the Associated General Contractors

booklet, Waste Disposal and Erosion and Sediment Control Methods,

by calling (206) 284 -0061. Read the booklet and share it with

your builder. If

you build a new home, ask your builder to leave as much of the

original vegetation as possible on site. Before you start construction

grading, acquire a copy of the Associated General Contractors

booklet, Waste Disposal and Erosion and Sediment Control Methods,

by calling (206) 284 -0061. Read the booklet and share it with

your builder. |

Permeable

Paving Surfaces

Because so many of our human landscape features are impervious,

a few words about using paving surfaces that allow rainwater to

soak into the ground seem in order. There are many materials that

provide the durability of concrete while allowing rainwater to

filter into ground.

Bricks,

interlocking pavers, precast concrete lattice pavers, or flat

stones make an attractive, durable walkway. If placed on well

drained soil or on a sand or gravel bed, these modular pavers

allow rainwater infiltration. To control weeds growing in the

spaces between the pavers, consider Corsican mint or moss as a

natural way to crowd out weeds and add beauty to the paved area. Bricks,

interlocking pavers, precast concrete lattice pavers, or flat

stones make an attractive, durable walkway. If placed on well

drained soil or on a sand or gravel bed, these modular pavers

allow rainwater infiltration. To control weeds growing in the

spaces between the pavers, consider Corsican mint or moss as a

natural way to crowd out weeds and add beauty to the paved area.

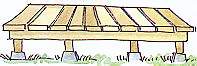

Wood

decks, usually installed for their functional good looks, can

serve as a form of porous pavement. Redwood, cedar, or treated

wood are as durable as most other paving surfaces. The spacing

in the decking allows rainwater to drain directly onto the soil

surface and soak into the ground. Maintaining the distance between

the soil surface and the decking recommended by your county building

department will minimize risk of wood rot. Wood

decks, usually installed for their functional good looks, can

serve as a form of porous pavement. Redwood, cedar, or treated

wood are as durable as most other paving surfaces. The spacing

in the decking allows rainwater to drain directly onto the soil

surface and soak into the ground. Maintaining the distance between

the soil surface and the decking recommended by your county building

department will minimize risk of wood rot.

New, porous

materials are also becoming available. For example, porous asphalt

is similar to conventional asphalt in durability and cost. You

can use porous asphalt on your new driveway and encourage its

use on streets and parking lots in your community. For specifics,

call the Washington office of the Asphalt Institute at (859) 288-4960

or the Washington

Department of Ecology at (360) 407-6000..

|

|

|